The name Banff was chosen by a number of the town’s Scottish founders who were from Banffshire, Scotland (the name in Gaelic can be translated as holy woman) while the local Stoney Nakoda peoples call the area Mînî hrpa meaning “Mountain Where The Water Falls” after Cascade Mountain which resembles a cascading waterfall of rock, snow and ice.

Across the valley, Sulphur Mountain is called Mînî Rhuwîn (translates as foul-smelling water) by the Stoney Nakoda. They used the many hot springs that bubble up from the mountain for healing and they climbed the mountain to harvest numerous medicinal plants, most notably the bark from the Whitebark Pine that grows in subalpine areas.

Mount Rundle is known as Waskahigan Watchi or “House Mountain” by the Cree. Tunnel Mountain is referred to as the “Sleeping Buffalo” by the Stoney Nakoda as it resembles a sleeping buffalo when viewed from the north and east. There is a growing movement to rename it to Sacred Buffalo Guardian Mountain (feel free to sign the petition here).

Indigenous History of Banff National Park

Over 450 indigenous archaeological sites have been discovered in Banff National Park that involve points, stone tools, spears, butchered bones, hearths, house pits and pictographs.

The oldest archeological discovery in Banff National Park was a Clovis point found along the shores of Lake Minnewanka just outside of Banff, dating to 13,000 years ago. The Stoney Nakoda refer to the lake as “Minn-waki” or “Lake of the Spirits”, a place they both respect and fear for its resident spirits.

As you drive from Calgary, you will enter the lands of the Stoney Nakoda in the foothills just before you enter the mountains. The Stoney as well as other First Nations tribes would often migrate with the seasons through the valleys and passes of Banff National Park and spend the winters in the warmer lowlands to the east or west of the Canadian Rockies.

Historically, the mountainous areas that now make up what we now call Banff, Kootenay, Jasper and Yoho National Parks were important meeting places where regular trading occurred among a number of different First Nations cultural groups.

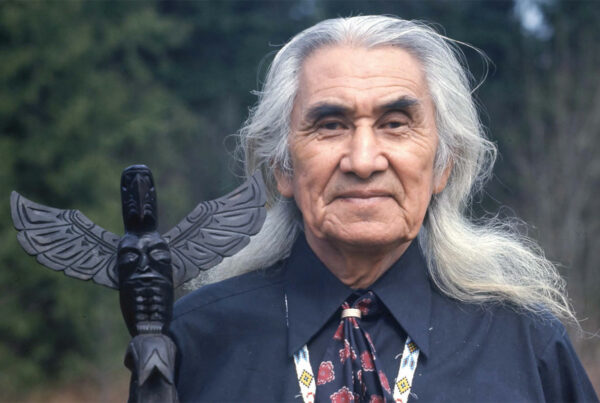

For these First Nations peoples, the Canadian Rockies are considered a sacred place and are known to be the land of the spirits or mysteries. Here’s how Chief John Snow of the Stoney Nakoda describes the Rocky Mountains:

“These mountains are our temples, our sanctuaries, and our resting places. They are a place of hope, a place of vision, a place of refuge, a special and holy place where the Great Spirit speaks with us. These mountains are our sacred places.”

First Nations Peoples of the Canadian Rockies

Here are the different First Nations people who once lived in Banff National Park and how you can learn more about their culture and traditions where they live on both the Alberta and British Columbia sides of the Canadian Rockies:

1. Stoney Nakoda

The Stoney Nakoda (pronounced Stow-nee Nah-koh-duh) are also known in their own language as the Iyârhe (ee-YAH-hhay) which means “Peoples of the Mountains”. They came to be known as the Stoney by Europeans because of their use of heated stones to cook their meals.

Traditionally, the Stoney Nakoda roamed the lands along the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains stretching from the edge of today’s Glacier National Park in Montana to the North Saskatchewan River and west to the Continental Divide.

They comprise the following 5 bands:

• Bighorn

• Bearspaw

• Chiniki

• Wesley

• Eden Valley

The Stoney Nakoda are the First Nations people most associated with Banff National Park. They were removed from the mountain areas and restricted from hunting animals and gathering plants soon after the park was created in 1885.

Just off the Trans-Canada Highway 1 (Exit 131) outside of the small town of Mînî Thnî (also known as Morley) as you are approaching the Rocky Mountains is the Chiniki Cultural Centre, which is an excellent place to learn about the history and culture of the Stoney Nakoda people (it’s inside the Smitty’s restaurant).

There are also some good cultural and historical displays at the Stoney Nakoda Resort & Casino, which you will pass by just before you enter the mountains at Mount Yamnuska, which provides the backdrop for the resort.

Yamnuska derives from the Stoney Nadoda name Îyâ Mnathka, meaning “flat-faced mountain”. However, Yamnuska is a misspelling and translates to “messy hair” (the proper name is Mount E-Yamnusak).

They speak the northern dialect of the Dakota language, a division of the Siouan language group that is spoken across the Great Plains, Ohio and Mississippi valleys and southeastern North America.

Learn more about the Stoney Nakoda history of Mînî hrpa in this excellent short film made as part of the recent Moving Mountains Initiative.

2. Ktunaxa

The name of Kootenay National Park comes from the Ktunaxa Nation (pronounced K-too-nah-ha) also referred to as the Kootenay people who are made up of the following four bands:

• Akisqnuk (also known as the Columbia Lake First Nation)

• Yaqan Nukiy (also known as the Lower Kootney Band)

• Aq’am (also known as St. Mary’s First Nation)

• Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi (also known as Tobacco Plains Indian Band)

Their traditional lands are in the watersheds of the Columbia and Kootenay Rivers along the western slopes of the Rockies. They are often referred to as the People of the Salmon since salmon fishing was their key food source while the First Nations on the eastern slopes of the Rockies are often referred to as the People of the Buffalo as the buffalo was their most important food source.

In the United States, there are two other Ktunaxa bands where they are referred to as the Kootenai people and they live along the Kootenay River, which flows from British Columbia down through Montana and Idaho.

One of the most prized trade items of the Ktunaxa people was red ochre that they would collect from the sacred Paint Pots found in Kootenay National Park. Ochre was used to paint important symbols on rock, teepees and clothing.

Traditional Knowledge and Language Coordinator Lillian Rose highlights Ktunaxa connections to the land and waters of Kootenay National Park in this short film Our land, our story, our words. She reflects on how park establishment has impacted their freedom to know and be intimate with the land.

3. Niitsitapi or Blackfoot

There are three branches of the Blackfoot peoples in Alberta, who call themselves “Niitsitapi” (pronounced nee-itsee-tah-peh) meaning “the real people.” They are made up of the following three bands in Alberta:

• Siksiká Nation (pronounced Six-ih-gah) also known as the Blackfoot.

• Kainai Nation (pronounced Gaa-nah) also known as the Bloods or Káínawa.

• Piikani Nation (pronounced Be-gun-nee) also known as Aapátohsipikáni or Northern Piikáni.

Two key areas of the Blackfoot culture are the confluence of the Elbow and Bow Rivers near where Calgary’s downtown sits and Blackfoot Crossing about 100 km further down the river, which were the two main fords for crossing the lower Bow River that became important gathering points to exchange goods and celebrate festivities.

The largest reserve in Canada is the Kainai Nation lands, which is 1,342.9 km² between the city of Lethbridge and Pincher Creek in Southern Alberta.

The Siksiká Nation has the second largest reserve in Canada about 100 km east of Calgary just off the Trans-Canada Highway 1. You can learn about the history and culture of the Siksiká people at the excellent Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park, which was the site of the 1877 Treaty No. 7 signing on the hills above the Bow River.

This documentary from the Shining Mountains series follows mountain guide, pilot and cinematographer Guy Clarkson on an ecological journey through the Rockies and talks about the sacred hunting grounds of the Blackfoot nations in the Rockies.

4. The Tsuut’ina

The Tsuut’ina Nation (pronounced Sue-tin-ah) means “many people” or “beaver people”. They were formerly called the Sarsi or Sarcee, derived from a Blackfoot word meaning “stubborn ones” who they were in constant conflict with over territory. Because of its origin from a rival First Nations group, the term is now viewed as offensive by most of the Tsuutʼina.

The Tsuutʼina language is an Athabaskan language that is closely related to the languages of the Dene groups of northern Canada and Alaska, and also to those of the Navajo and Apache peoples of the American Southwest. This is in contrast to the geographically nearer Blackfoot language and the Cree language, which are Algonquian languages spoken across Canada and the United States.

They operate the Tsuut’ina Culture/Museum and Grey Eagle Resort & Casino on their reserve lands that border the southwestern city limits of Calgary and stretch west to eastern Bragg Creek, Kananaskis and the Moose Mountain area.

This short film explores the culture, traditions and history of the Tsuutʼina Nation and their long rivalry with the Blackfoot Nations.

5. The Sushwap or Secwépemc

The Sushwap Nation (pronounced shoo-swaap), also referred to as the Secwépemc are a Salish-speaking people that border Jasper National Park. They are also mixed with the Ktunaxa and make up one of the largest indigenous First Nations groups in British Columbia.

The Shuswap language is the northernmost of the Interior Salish languages, which are spoken in the Pacific Northwest region of Canada and the United States and are a branch of the larger Salish language group (also referred to as Salishan) that is widely spoken on the coast of British Columbia.

Banff was a winter village of the Sushwap. They built semi-subterranean homes called pit-houses or kekuli just downstream from Bow Falls.

Shuswap Band Elders Laverna and Louie Stevens share their thoughts on the land and waters that are now part of Kootenay National Park in this short film collaboration with Parks Canada.

6. Métis Nation

The Métis people are a post-contact Indigenous nation, born from the unions of European fur traders and First Nations women in the 18th century.

The Métis people are a post-contact Indigenous nation, born from the unions of European fur traders and First Nations women in the 18th century.

Alberta is home to more than 127,000 Métis people and is the only province in Canada with a recognized Métis land base. There are 8 Métis Settlements in Alberta, comprising 5121 km² and Métis peoples have travelled through and lived on both sides of the Canadian Rockies for over 200 years.

These are the main indigenous First Nations groups associated with Alberta’s Banff National Park and the Treaty 7 territory.

Jasper National Park is located in Treaty 6 and Treaty 8 territory. It is the traditional territories of the following First Nations:

• Beaver

• Nehiyawak (Cree)

• Ojibway

• Salishan (Shuswap)

• Stoney Nakoda

• Métis

This short video explains the origins, diversity and controversies surrounding Métis people in Canada.

Where To Learn More About Local First Nations In The Bow Valley:

1. If you want to learn more about local First Nations perspectives, I highly recommend reading Stoney Nakoda Chief John Snow’s classic book These Mountains are Our Sacred Places: The Story of the Stoney People.

2. Support local First Nations nonprofits in the Bow Valley like Soul of Miistaki, which was founded by a Blackfoot woman living in Canmore with the intention of offering diverse people an inclusive experience of the outdoors.

3. Another local nonprofit Spirit North in the Bow Valley helps transforms the lives of Indigenous youth by inviting them to discover their strengths through sport and play.

4. The Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies has put together excellent recommendations for learning more about Indigenous Life in Banff.

5. The Buffalo Nations Luxton Museum in Banff is also worth visiting to learn about the First Nations history and culture of the area.

6. Native Land is a resource to learn more about Indigenous territories, languages, lands, and ways of life.

7. The University of Alberta offers an excellent 12-lesson online course about Indigenous Canada on Coursera.

8. I’m a big fan of watching documentary films to go deeper into interesting topics. Here are 25 excellent documentaries about First Nations and Native American History.

9. Educate yourself about by watching the 8th Fire documentary series and familiarizing yourself with the 94 Calls To Action for Truth and Reconciliation.

I hope you found this post educational and that it sparks your curiosity to learn more about the First Nations people in the Bow Valley and along both sides of the Rocky Mountains in Western Canada.

- Chephren Lake And The Mistaya River Valley - July 1, 2024

- Mindfulness And The 4 Steps of Attention Restoration Theory - June 29, 2024

- 3 Pillars Of An Ecotourism Marketing Strategy For Selling Travel Experiences - June 29, 2024